Indigenous People in Chicagoland

March 27, 2023

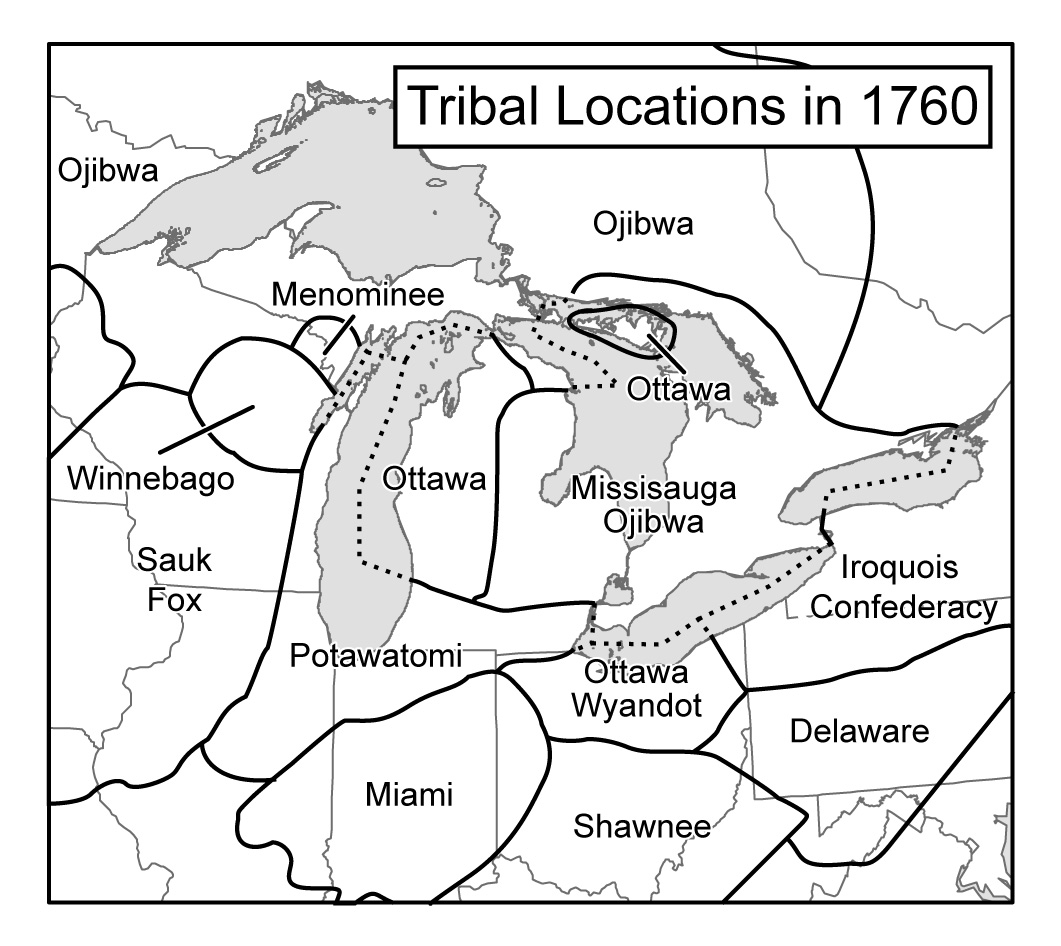

Skokie Public Library is built on the homeland and trading ground of many Native American people and tribes, including the Council of Three Fires (the Ojibwe, the Potawatomi, and the Odawa), and many other nations, including the Menominee, the Ho-Chunk, the Miami, and the Sauk.

Skokie sits in the Great Lakes region of the Americas. Historically, this area had rich soil, abundant animal and plant life, and Lake Michigan. Plentiful food meant that the various tribal nations with settlements here, or that regularly passed through the area, rarely had conflict over resources. Instead, it became a place of cooperation and trade. Professor John Low of Ohio State University describes this space as a place of gathering, as well as a place for the exchange of items, ideas, and agreements. What we now call the Chicagoland area, including Skokie, was a crossroads for the Indigenous tribes that made their homes across the Midwest.

The appearance of European colonizers didn’t initially affect that dynamic of cooperation. The abundant resources meant that there was enough to support the additional individuals and small groups that migrated west. However, as more and more people arrived and the newly formed American government began to look for more land, things began to change.

Increased hostilities and armed conflicts, including those associated with the French and Indian War and the War of 1812, both of which had Native Americans on both sides of the conflict, as well as an increase in colonizers, began to sour relationships. The United States government was determined to expand its territory, which it did over the 18th and 19th centuries.

Through a series of coercive treaties made by our country’s leaders, who were willing to use predatory methods to force agreement, tribal nations were made to cede more and more of their land. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, fulfilling an election promise. In 1833, Indigenous leaders were made to sign the last Treaty of Chicago. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi was able to stay in Indiana and Michigan due to their connection with the Catholic Church, but all other tribes were forced west of the Mississippi on what became known as the Trail of Death.

Today, there is no federally recognized tribal land in Illinois.

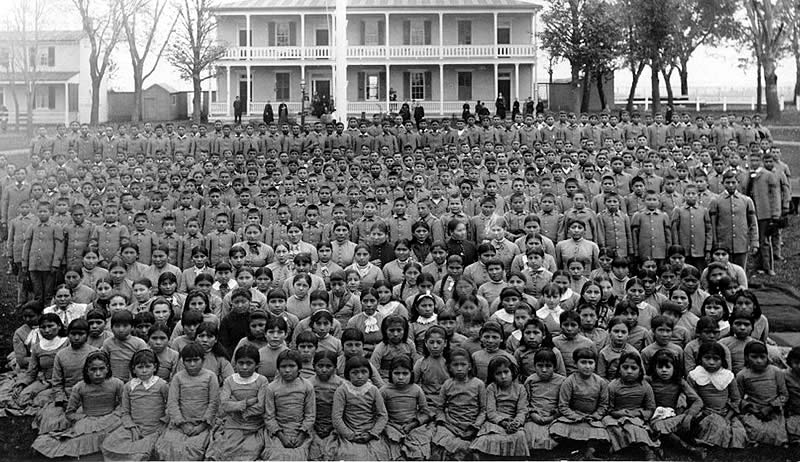

In the 20th century, the United States government’s methods shifted, though the goals did not. Where once the government had sought to remove Native Americans by placing them on reservations, the government began attempting to remove them through assimilation instead. By enacting the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, the government sought to free itself of treaty-mandated obligations to support tribal lands and the populations of Native people living there, as well as to solve labor shortages brought about by industrial booms in cities like Chicago.

Tribal populations were encouraged, often without good options for refusal, to relocate to cities far away from their reservations, to live away from other Native Americans, and to assimilate into the culture and needs of the United States. The American Indian Center in Chicago was founded partly in response to this. When Indigenous Americans were given train tickets to Chicago and then essentially abandoned, the Chicago population banded together to create a sense of community and promote the welfare of urban Indians in spite of the government’s desire to destroy tribal culture.

There’s often a perception that Native Americans live exclusively, or even largely, on reservations. This is far from true. According to data from 2010, 78% of all Native Americans and Native Alaskans do not live on reservations. Cook County is 19th on the list of counties with the largest population of Native residents, a list that includes a mix of urban and rural communities. There are now almost 22,000 Indigenous Americans residing in the city of Chicago, either because of the American government's history of coercive relocation or their own desires. In the last census, nearly a thousand of Skokie’s residents identified themselves as having Indigenous ancestry. More than 300 residents are listed as American Indian or Native Alaskan alone.

This blog post barely scratches the surface of Indigenous history for Skokie and the Chicagoland area, and while it’s certainly important to investigate that history more deeply, we have a tendency to solely view the experiences of Native Americans as just that—history. The Indigenous population of the Americas still very much exists, not just on the reservations the American government fails to support, but here, in Illinois, in Chicago, and in Skokie. The experience of American Indians and Alaskan Natives is far from monolithic, but it’s also still evolving.

The persecution, racism, and theft that characterize their history with colonial America continue to affect that experience today, and while the Native American community is active in fighting against those injustices, discussions of inequity often fail to include them. The past informs the future, but so does the present and the work we do today.

Here are some resources to help you learn more.

From our catalog:

- Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, Pekka Hämäläinen. (2022)

- Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America, Michael A. McDonnell. (2015)

- An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. (2014)

- Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago, John N. Low. (2016)

Recorded events from area libraries:

- An Indigenous History of the Upper Great Lakes Region, Session 1 and Session 2 (Evanston Public Library)

- Author John N. Low, Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago (Chicago Public Library)

- Whose Lakefront: Chicago's Unceded Native Land (Chicago Public Library)

Local community groups: